|

We don’t give it to U.S. presidents or to corporate CEOs: Although we install them with great ceremony, in a few years, most are gone. We don’t give it to plumbers or police officers: They have to perform to keep their jobs. Queen Elizabeth II and Emperor Akihito have it, though what they do each day is highly constrained. But university professors can do with it what they wish, without review, for life. We call it tenure.

One hundred years ago, the American Association of University Professors endorsed a “Declaration of Principles” regarding academic freedom and tenure. Academic freedom in the United States has produced 357 Nobel Prizes; 9 of the 10 most innovative universities on the planet, as ranked by Reuters; and a vibrant, creative higher-education system. Academic tenure, meanwhile, produces stultifying intellectual uniformity, protects incompetence, generates mountains of useless “research” and leads to undergraduate teaching done by poorly paid part-time adjuncts and graduate students. Tenure is not, as was its original intent, protecting the freedom to teach controversial subjects; it is protecting the right to offload teaching onto underlings. This isn’t freedom to pursue research wherever it leads; it’s the right to publish irreproducible studies and uncited scholarship. Many of my tenured colleagues are excellent undergraduate teachers — when they are not on sabbatical, research leave or an exemption from teaching duty, or leading graduate seminars. Most are outstanding researchers: as good as the untenured staff and graduate students with whom they work, but not worlds better. Is tenure what motivates and protects their teaching and scholarship? No. Would our universities be more equitable, more agile and more focused on the students who pay the bills without tenure? Undoubtedly. Tenure protects behaviors that diminish our universities. It is an anachronism we can no longer afford. That’s why, when offered, I turned it down. Academic freedom and tenure are not synonymous. You can have one without the other, and it is high time we did.

2 Comments

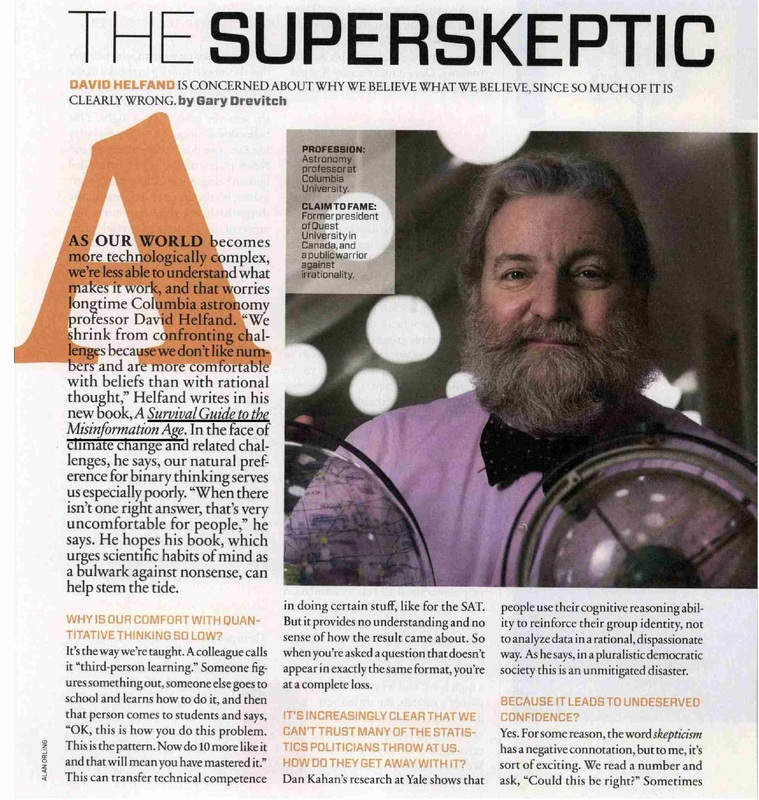

Question: Most people think we are living in the Information Age. Why the contrarian “Misinformation Age” in your title?

DJH: It is certainly true that the amount of information abroad in the land is unprecedented, and the internet democratizes access to this information in ways that are unique in human history. But we are now generating, worldwide, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data per day. If printed in standard characters, that’s the equivalent of 450,000 pages of text per person per day. Obviously, more than 99.99% of this “information” is not edited or vetted for accuracy. And the corollary of open access to the web for downloading information applies equally well to uploading information. The result? Unlimited opportunities for the propagation of misinformation and unfettered access for individuals and organizations to spread disinformation. Q: Surely misinformation isn’t new, nor is the motivation of some to spread disinformation to advance vested interests. Why do you suppose the problem is greater today? DJH: Two reasons. First, during the first 97% of the time members of our species homo sapiens have roamed the Earth, information was very limited but the important bits were generally of high quality. The member of the hunter gatherer tribe who regularly led hunting parties toward the hungry lions instead of the zebras was quickly ignored (or eaten and eliminated from the gene pool; likewise with the one that gathered poisonous fruits). The sources of information — your clansmen — were unambiguous and there was an existential premium on good information. Today the sources are anonymous, or at least often unknown to you, and their motivation for providing accurate information is negligible; there are no consequences for misinformation nearly as severe as the lions. Thus, if mis- or dis-information serves one’s purposes — either for accumulating money or power, or for the strong innate motivation for reinforcing group identity — there’s no barrier to broadcasting it. Couple this with the viral tendencies of social media and the instant accessibility of nonsense for all, and you have what I think should rightly be called the Misinformation Age. Q: Accepting your premise for the moment that misinformation is rife on the internet, does it really matter? Are there any practical consequences of concern? DJH: Indeed there are — dire consequences, both for making individual decisions about finances and health, and for the formation of rational pubic policy. I cite several examples in the book. Consider the ‘vaccination leads to autism’ myth. The original study that led to this claim was unequivocally shown to be fraudulent (not just wrong, but generated in order to profit the principal author). The article reporting this result has been retracted by the journal and the author barred from practicing medicine; furthermore, many subsequent studies have shown absolutely no link between childhood vaccination and autism. Nonetheless, hundreds of websites exit to reinforce this bogus notion and large segments of the population believe it. In California, kindergartens exist in which fewer than 30% of the children attending have had their shots, because California allows a “personal belief exemption” for parents who choose not to vaccinate their children. Between 2001 and 2010, there was an average of 45 cases of measles a year in the US, nearly all of which arrived from other countries. In 2011, the number was 220 cases and in 2014 it jumped to 667 cases, almost all among unvaccinated domestic children, with the largest number in California. Or take climate change if you aren’t concerned about sick and dying children. The Chairman of the Senate Committee on the Environment has labeled it a “hoax” and has brought snowballs into the Senate chamber to buttress his case. In this instance there are thousands, if not tens of thousands of websites propagating misinformation on the subject, not to mention the many more that are designed to generate disinformation to protect financial interests. Just listening to the current political discourse on this topic is should be enough to convince you it’s the Misinformation Age. Q: Well, yes, that is a case where 97% of scientists agree that hurricanes are getting stronger… DJH: Ah, you see! You just added to the propagation of two totally bogus statistics. In fact, the 97% figure comes from a 2013 article in Environmental Research Letters by Cook et al. Writing in The Skeptical Inquirer (Vol. 39, No. 6), J.L. Powell shows unequivocally that the methodology adopted by Cook et al. grossly underestimates the level of consensus. A complete review of all papers published in refereed journals in 2013 and 2014 that have titles or abstracts with the terms “global climate change” and/or “global warming”, shows that five out of 24,210 reject anthropogenic global warming (two of the five are by the same author, and only one of the five has a single citation, ignoring self-citations). Looking at all the authors of all those papers, four out of 69,406 or 0.0058% deny human-induced climate change. So the correct number is greater than 99.99% of scientists are part of the consensus, a qualitatively different statement than 97%. As for hurricanes, you’ll have to read the details in the book, but in the last forty years, a period of unprecedentedly rapid warming, the number of Category 3-5 Atlantic hurricanes has decreased over the previous 40 years. Just because there are a thousand websites that reiterate these statistics, and they are constantly repeated by social and traditional media, does not make them true. That’s the essence of the Misinformation Age. Q: What is your proposed solution to this misinformation glut? DJH: Read my book. The fast-changing, technology-dominated world we live in is not the world our brains evolved in. They are not, therefore, well-adapted for carefully sifting through large quantities of often abstract information, assessing it through skeptical questioning, and then combining it in useful ways. We do, however, have a processor, the prefrontal cortex, that is capable of such deliberate, rational decision making. But it needs to have the right apps installed. That’s the point of my “Survival Guide”. As Neil deGrasse Tyson says in his review, such an approach is essential since “the future our civilization may depend on it.” Commenting on one of the recent string of articles in the New York Times discussing the collapse of world oil prices, a reader wrote:

“The cost of a barrel of oil drops by 75% and the cost of a gallon of gas drops by 25%. Somebody somewhere is making billions on the backs of American consumers.” This, indeed, sounds like a major discrepancy, and I have no doubt many readers agreed with this commentator’s analysis. After all, it fits the current tropes of evil big oil companies, growing wealth inequality, and the fact the average consumer never gets a break. Unfortunately, the logic is faulty and the conclusion is wrong. While this particular example is not of great import, it is symptomatic of the innumeracy and illogic that is rife in our society and that cripples our ability to make rational public policy decisions. For the record, here’s a correct analysis of the data in the article. A barrel of oil contains 42 US gallons (I will refrain here from my usual diatribe about the continued use of irrational US units). The average price of West Texas Intermediate crude (the US benchmark) in 2013 was $97.98 per barrel, within a dollar or two of the highest annual average price ever recorded (that was in 2008). This means that the average gallon of oil in 2013 cost $2.33. If the price had actually fallen 75%, the cost of that same barrel today would have been $24.50 and the market has not yet hit that level; in recent weeks it has been hovering around $30.00 a barrel, meaning the average gallon of oil purchased this month cost about $0.71. That’s a drop of more than a factor of three — obviously much bigger than the decline of gas prices at the pump. However, your local gas station pump does not deliver West Texas Intermediate crude. The oil (that’s the price on the ground at Cushing, Oklahoma, by the way) must be transported to a processing facility, be refined into gasoline and other products, have various additives mixed in, be transported to your local gas station, and be sold there, with federal and state taxes included. In fact, the average gasoline price in the US in 2013 was $3.49 a gallon. Subtracting the price of the oil, that leaves $3.49-$2.33 = $1.16 to cover all those costs plus the profits of any entities involved. During the last week of January this year, the average national gas price was $1.804 (down 48%, not 25%, by the way). Subtracting the current price of oil, the net cost is $1.09, a few cents lower than in 2013. So much for profits at refineries, pipeline companies, trucking companies, and gas stations. There are still the producers at the wellhead who were getting a lot more money in 2013 for their product. Then, they may have been making “billions”. However, on average, it costs more than $30 a barrel to produce a barrel of oil in the US. That’s why Exxon-Mobil’s fourth quarter profits fell by a factor of two from a year earlier, why it lost more than half a billion dollars on oil production in three months, and why, by late January, Facebook had a larger market capitalization than Exxon-Mobil, which until a few years ago was the largest company in the world. Meanwhile, Royal Dutch Shell’s profits were down 56% and BP lost $3.3 billion dollars in the quarter. The point of this analysis is not to generate sympathy for big oil companies, especially ones that deliberately contribute disinformation to the debate on climate change. My points are a) that plausible sounding statements, especially those that fit our pre-conceived notions, can be very wrong, and b) that the virtually unlimited power of the Internet to propagate such faulty information has launched us into the Misinformation Age. The advent of the Internet and the ease of entry to it provided by the World Wide Web have led to an explosion of information and a radical democratization of access to that information. Simultaneously, however, unfettered, unfiltered access to the Web means that there is no judgment exerted over what constitutes valid information appropriate for worldwide distribution. As a result, misinformation flourishes and deliberate disinformation is granted a completely free path (free of obstacles and free of cost) to propagate effectively. As Tom Nichols points out in his essay “The Death of Expertise”, we are in serious danger of living in a culture in which “everyone’s opinion about anything is as good as anyone else’s”. Senator Jim Inhofe, Chair of the Senate Environment Committee, has a “right” to his view that scientific evidence for climate change is “a hoax”. Michael Crichton, the novelist, is an appropriate “expert” witness for House climate change hearings. Jenny McCarthy’s “mommy instincts” should be granted respect equal to that of peer-reviewed medical research when it comes to the purported link between vaccination and autism. As Nichols notes, this radical egalitarianism is dangerous because it is “ a rejection not only of knowledge, but of the ways in which we gain knowledge.” Five thousand years ago, it didn’t matter if individuals or groups held beliefs disconnected from reality (although, it should be noted, in important matters such as securing food, shelter, and safety, at most a few people did, and those few no longer contribute to the gene pool). Even five hundred years ago it didn’t matter much: either Columbus would sail off the edge of the world and land on the turtle holding it up or he wouldn’t. Today, however, with 7.4 billion people occupying almost every ecological niche on the planet and placing demands on the Earth that are patently unsustainable, it matters – a lot. Without the capacity to make individual decisions and to enact public policies based on verifiable facts rather than individual fantasies, without the acknowledgement that some ways of knowing have a demonstrably better track record than others, the future looks grim indeed. Search engines spit back rational views and nonsense with equal rapidity. It is only by adopting a healthy skepticism to the tsunami of incoming information and by assessing it through the logical application of successful modes of analysis can we hope to thrive as a species at this unique moment of our planet’s history. |

AuthorDavid J. Helfand writes on education, climate change, astronomy, and the impact of misinformation on personal decisions and public policy. Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed